If an accountant does your taxes, how do you know that her advice is sound? If you visit a new dentist and she says you need a filling replaced, how do you know if she’s right—and competent to do the work? If an electrician tells you your home’s wiring is dangerously out of date, how do you know if he’s telling the truth—and knows how to rewire the house safely?

Well, ultimately, you don’t. Accountants, dentists, and electricians are sometimes wrong. And some are better at their work than others. (It pays to ask around.)

But in nearly every state, you can be assured of three things. First, these people are trained in what they do. That is, they have been to school to learn accounting, dentistry, or electrical repair. Second, they have demonstrated their knowledge in a test, so you know they are competent to do the work. Finally, if things go badly, you can complain to a state agency that has the power to discipline these professionals

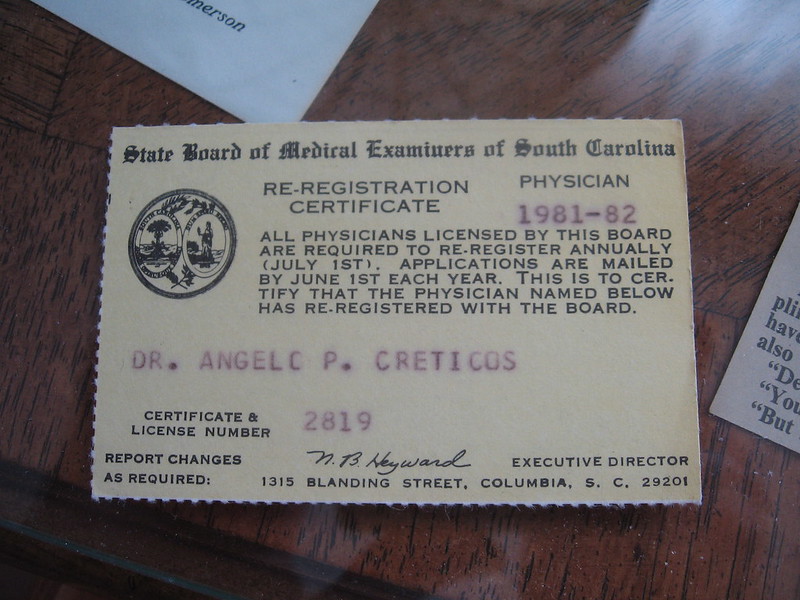

And all of that happens because states license some lines of work. So, if you want to be a doctor, lawyer, civil engineer, nurse, plumber, long-haul tractor trailer driver, funeral service director, financial planner, or insurance sales agent you have to be licensed in most states.

One more bit of reassurance: As mentioned above, the licensing process starts with training, often by graduating from an accredited school, but the training can go on indefinitely. Some states demand that certain professionals take additional courses called continuing education units, to retain their licenses. The aim is to be sure they don’t lose basic skills and stay abreast of new developments.

Does licensing work? Do we have better dentistry today than we might have had if we had not required dentists to take courses in dentistry, pass an exam, agree to mid-career training, and accept discipline if they failed in their duties? Has requiring electricians to be licensed saved buildings from burning down? Has licensing civil engineers prevented some bridges from collapsing?

We can’t know for sure because it’s impossible to prove counterfactuals. That is, we can’t go back in history, remove all the licensing laws, and see how things turned out. Nor do we have a state bold enough (or, some would argue, crazy enough) to tell anyone who wants to be a dentist, doctor, or lawyer to hang out a shingle and let the buyers beware.

But we do know two things. First, not everyone who takes professional exams passes them, which indicates licensing does screen out some who really shouldn’t be lawyers, doctors, or plumbers. In California, for instance, 44 percent of law-school graduates taking the bar exam do not pass. (Don’t worry. Plenty of others do. There are more than 170,000 lawyers in California, which is the 10th highest per capita rate of lawyers to residents in the country.)

Second, professional discipline does weed out some who are competent but corrupt or suffer from some other failing that endangers clients. In 2017, 4,081 physicians were disciplined by state medical boards, which included everything from reprimands to license revocations. (That year, 264 doctors had their licenses revoked, 570 voluntarily surrendered their licenses, and another 794 had licenses suspended for a period of time.) The statistics for lawyers are less complete, but we know that in 2018 more than 2,870 lawyers were disciplined by state bar associations, acting on behalf of state governments. (Of those, 630 were disbarred, which took away their license to practice law.)

In short, then, licensing stops some people from taking jobs that they’re not qualified for, and it can weed out those who show by their actions that they are no longer fit to do important work. In doing so, licensing almost certainly raises professional standards and makes citizens safer.

So, when did states start licensing professions, and why? There were earlier attempts, but most states did not begin licensing lawyers, doctors, and others until the late 1800s. But once most states had started licensing professionals, others followed in short order.

Why? Three reasons: First, supply began catching up with demand. That is, medical schools, law schools, and engineering colleges started turning out enough trained professionals to fill the demand for medical, legal, and engineering services.

Second, these newly-minted doctors, lawyers, and engineers were appalled by the quackery and fraud they saw around them. How do you convince a patient to accept surgery if a homeopath had convinced her that the oil from a pine tree cures cancer? So the professions themselves became a force for licensing.

Third, there was a rise of expertise in America. As we saw in earlier entries, the late 1800s were a time of industrialization, education, and urbanism, and Americans came to recognize that the systems behind urbanism needed people trained in designing factories, building railroads, constructing subway systems, reducing the spread of disease, and interpreting the laws that governed these things. And it wasn’t just in cities that expertise gained acceptance. Agriculture, too, saw a rise in professionalism, thanks to land-grant colleges and cooperative extension.

Rightfully, states concentrated on licensing professions that had one or more of three qualities. First, they involved citizens’ health or safety. This is the reason doctors, electricians, and long-haul truck drivers are licensed. Second, they involved “asymmetric knowledge,” which is a fancy way of saying that these professions know a great deal about a highly specialized subject about which average people know little. As a result, most of us must trust professionals to tell us the truth and carry out their duties faithfully. This is why lawyers and accountants are licensed. Third, they operate to some degree as agents of the state. People in the building trades are licensed because they must follow state and local building codes. If they ignored the code, they not only place people’s lives in danger, they also undermine government efforts to save water, increase energy efficiency, and prevent fires. Not many plumbers or electricians are willing to risk their licenses by deliberately not “building to code.”

So there are good reasons for licensing some professions. But libertarians have a point when they argue that state governments have gone too far in licensing. Today, nearly 30 percent of workers are in occupations requiring a license. That’s almost certainly too many. Nearly 1,100 occupations have a licensing requirement in at least one state but fewer than 60 occupations are licensed in all 50 states. Reasonable people can disagree about the specifics but we almost surely need closer to 60 professions to be licensed than 1,100.

Here’s a good rule of thumb: If the average person can look at a worker’s product or service and judge whether it is good or not (and the work involves little potential for harm to the customer), then that occupation probably should not be licensed. Besides, there is an alternative to licensing, which is certification. It works like a diploma. If you walk into a flower shop and see a certificate from the American Institute of Floral Designers, you can be assured that the person in charge of your table arrangement knows what he’s doing. You shouldn’t also expect to see a license from the state of Louisiana.

The excessive licensing shows us that any good thing can be made bad by going to extremes. And the licensing of professionals is clearly more good than bad. And for the good that licensing does—by making us more secure in wealth and health, and by giving us some assurance of justice if we are wronged—we can thank government.

More information”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Professional_licensure_in_the_United_States

Give the credit to: state governments

Photo by nsub1 licensed under Creative Commons.

Leave a Reply