We looked at elevators and how state and local inspections made this perhaps the safest mode of transportation around. Let’s widen the lens now and look at government’s larger responsibility for inspecting buildings and the “bible” that guides it, the building code.

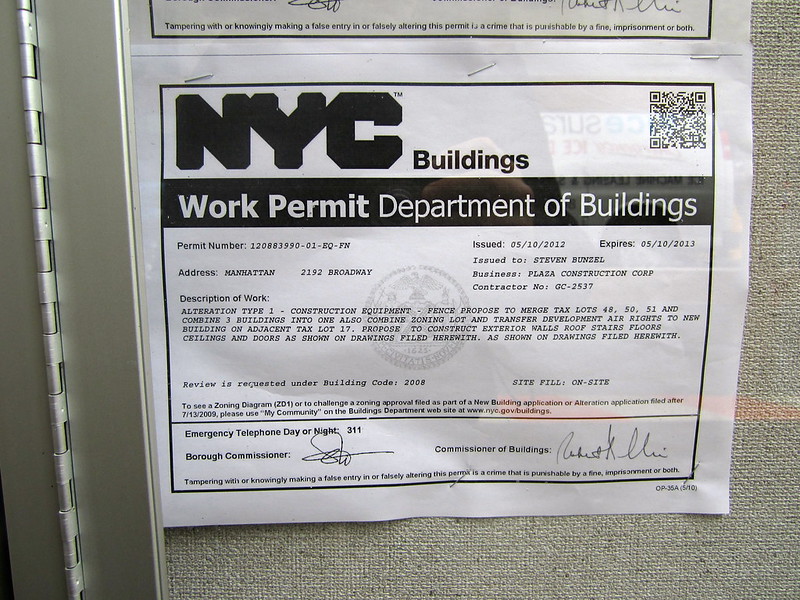

Building inspections occur when an office building, warehouse, single-family house, apartment complex, factory, or retail building is constructed or modified in a significant way, including changes to the electrical or plumbing systems. If you’re a homeowner and want to add a room, rewire your house, or build a garage, you have to get a building permit. And at some point during the remodeling, a building inspector will show up.

He or she will be looking for three things: First, is the work being done safely, so your house doesn’t burn down or the pipes burst? Second, does it follow the local building code, which often goes beyond safety and into measures that conserve energy and water? (In earthquake-prone places, the code may also require construction that can withstand a tremor. In coastal areas, it may require that buildings can stand up to a major storm.) Third, is the new construction reflected in the house’s tax assessment?

In commercial buildings, inspectors are concerned about safety, code, and assessments, but their reviews are more extensive because they involve public access. So they bring not only building inspectors but elevator inspectors and the fire department to review evacuation plans and test fire hoses.

There’s no question that these regulations add to the cost of construction. But they also bring benefits, preventing shoddy construction that could end in disaster and injury. And they may save you money over time, by requiring insulation that reduces energy costs and plumbing that saves water.

There’s another form of savings, which takes a little longer to explain. It has to do with “negative externalities,” which is the economic term for the things we do that have a cost to others but not necessarily to ourselves. Pollution is a classic example. If a factory can pollute the air or water but not pay for it, its owners have no incentive for changing their behavior.

Individuals can cause negative externalities as well, by wasting water or energy—or causing fires that bring a fire department crew roaring up to save things. If governments can act in ways that prevent the waste and head off disasters by requiring low-flow water devices in new construction, safe electrical wiring, rain gardens that capture storm runoff, efficient refrigerators and washing machines, and so on, then everyone benefits through lower costs for government services and utilities . . . including, ultimately, the homeowner.

This is why, whether you want them or not, your plumber will install low-flow toilets and shower heads. (Don’t worry. These low-flow devices work much better than in the 1990s when Jerry Seinfeld made fun of them.) And here, too, are two of the strengths of government. When government acts, it can bring steadfastness and scale.

Steadfastness is a way of saying that, unlike businesses, government tends to keep its commitments. And scale magnifies these commitments by applying them to everyone over time. You can see this in water usage in cities like New York, where overall consumption has declined—even as population has increased—and per capita usage has plummeted. In 1980, New Yorkers consumed 1,506 million gallons of water per day, which works out to 213 gallons per person. By 2019, overall consumption was down to 987.4 million gallons and 118 gallons per person. That’s a decline of nearly 45 percent in 30 years’ time. (Thank you, low-flow shower heads!)

What brought governments into the business of creating building codes and sending out inspectors to enforce them? The same reasons that brought them into the business of inspecting elevators: disasters (particularly from huge urban fires, like the Triangle Fire of 1911) and public pressure. Gradually, the codes evolved from preventing disasters to dealing with problems like water and energy consumption. And something surprising happened along the way: The codes became more or less uniform across the country—and far less contentious. Today, many interests are involved in shaping building codes, from builders, architects, and trade unions to state and local governments and large trade associations. Refining building codes is one of the most collaborative things that governments do.

So, if you’ve never worried about your home’s wiring causing a fire as you sleep, if you’ve noticed sprinkler systems and clearly marked exits at your workplace, if your city consumes less water and energy than it did two decades ago without anyone noticing, then you can thank government for creating building codes and enforcing them through intelligent building inspections.

More information:

https://www.eesi.org/papers/view/the-value-and-impact-of-building-codes

https://home.howstuffworks.com/home-improvement/construction/materials/building-codes.htm

https://www.nehrp.gov/pdf/UJNR_2013_Rossberg_Manuscript.pdf

Give the credit to: local governments 60%, state governments 40%

Photo by Daniel X. O’Neil licensed under Creative Commons.

[…] So two of the three kinds of farmers markets—the sprawling wholesale markets and iconic city markets—would not exist without government support, including financial assistance. But what about the neighborhood farmers markets, the ones that have grown so fast in recent years? This is where government usually acts as a collaborator, since few of these markets are owned by governments. Often they have nonprofit sponsors. But behind the scenes, local governments are deeply involved in helping out these neighborhood markets by closing streets, providing police protection, waiving business-license requirements for vendors, performing inspections for cleanliness and safety, sometimes even offering space free of charge. (Transit systems are increasingly making space available for farmers markets.) Governments are usually happy to do this because fresh produce helps with health issues like obesity, brings neighborhoods together, creates convenience for transit riders, and makes city life more affordable and enjoyable. These are positive externalities, a concept we’ve written about in our entries on public transit and building codes and inspections. […]