Crises move governments, and the greater the crisis, the greater the movement tends to be. We saw this in 2001, when the World Trade Center attacks caused major changes in airline security procedures and the creation of the federal Department of Homeland Security, and led to two long and frustrating wars. As the pandemic of 2020-21 recedes, we may see changes to public health and perhaps health care in general. And we saw this crisis-and-response phenomenon another time, in the early 1970s as a result of the 1973-74 oil embargo.

Too young to remember the embargo? It was an effort by Middle Eastern oil-exporting countries to punish the United States for supporting Israel in a war that began on Oct. 6, 1973. The embargo lasted five months, creating long lines for gasoline and fears that heating-oil supplies would dry up, and it awakened most Americans to two facts known before 1973 only to experts. First was the U.S. was heavily dependent on other countries for its energy supplies. Second was that petroleum, used for everything from transportation to plastics, was an exhaustible resource. The easy oil deposits had all been found; future ones would more difficult to tap and expensive to extract, and would involve environmental costs many were not willing to pay.

But what could the U.S. do? Two things that would take decades to realize. The first was to find additional domestic energy sources. Fifty years later, we’re still in search of these, although we are making great progress in renewable sources like solar and wind energy. The second task was to conserve energy, so we needed less of it to power our homes, cars, factories, and offices.

And that brings us to a government service that has, in some way, touched every American since the 1970s: the effort to encourage (and, in some cases, mandate) greater efficiency in everyday appliances and equipment, from dishwashers and refrigerators to air conditioners and automobiles. In this entry, we’ll look just at appliances. But you should know that the federal government’s efforts at conservation extend to motor vehicles (including electric and hybrid car models, buses that run on natural gas, and more efficient tractor-trailer trucks on the highways) and home and workplace insulation mandated by state and local building codes.

And you can trace all of these efforts back to the energy crisis of the 1970s. Before then, the federal government had no role in energy conservation. It didn’t even have a Department of Energy until 1977, when President Jimmy Carter created it. But in the years just before the department was created, efforts were already underway to make appliances more efficient.

These efforts began in California in 1974, when the state legislature set the country’s first appliance energy standards. Congress followed shortly afterwards by passing the Energy Policy and Conservation Act of 1975, which established a federal program of testing and labeling of consumer products. Other federal acts followed that, among the things, set minimum efficiency standards for appliances sold in the United States. If you’ve noticed that yellow-light incandescent bulbs of the 20th century have been almost totally replaced by brighter fluorescent and LED lights, you can thank the federal laws passed since the mid-1970s (or blame them, depending on how you feel about the glare).

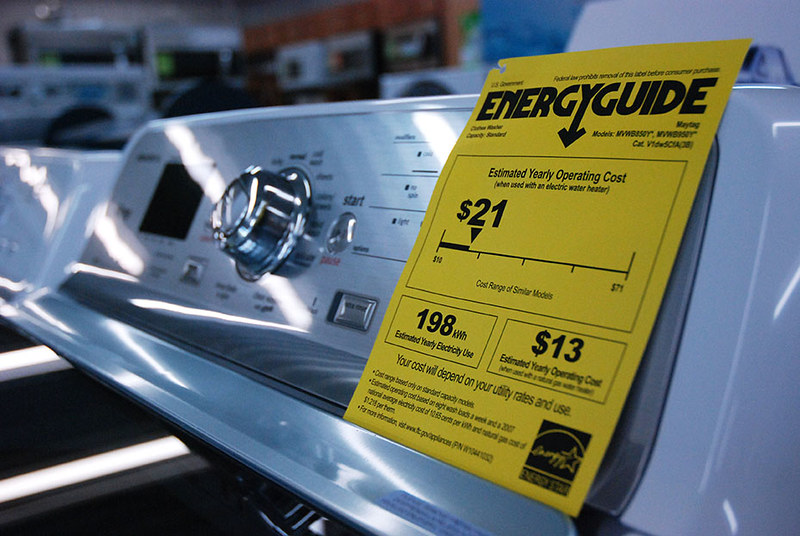

But perhaps the most obvious sign of the changes are the yellow and black stickers on appliances that arrived in the late 1970s. These are “EnergyGuide” labels. They’re required for scores of consumer products that consume significant energy, and are designed to help consumers understand the annual cost of operating appliances. So if you’re shopping for a dishwasher, you might see one model is $40 cheaper than another but costs $20 more a year to operate. Easy choice: Go for the more expensive but efficient model because, over the six to 10 years of a dishwasher’s life, you’ll save at least $80 and maybe as much as $160.

But the government’s intent isn’t to be a consumer adviser. It aims to save energy in ways that make America less dependent on other countries for petroleum supplies and helps reduce climate change. (These are “positive externalities,” which we’ve talked about in earlier entries about farmers markets, building codes and inspections, and public transit.) So, have these efforts reduced the amount of energy we use?

According to one nonprofit organization that studies these things, from 1990 to 2017, savings from energy conservation activities eliminated the need to build 313 large power plants and delivered savings of nearly $790 billion to Americans. This is more than just the appliance standards (again, transportation and building insulation also contributed) but appliances played a big role. Here’s another way to see the savings. In the early 1970s electric power consumption was growing by 7 percent a year. Today power consumption is flat or declining slightly, even with a larger population. That is almost due almost entirely to government energy standards.

Final thoughts: It’s worth noting that the government’s roles in energy conservation include those of tester and standard-setter. Consumers and manufacturers trust government to do an honest job in testing appliances for their energy consumption and labeling them correctly. Would they trust a trade organization or a private company to measure things accurately and tell the truth about their findings? Probably not. (We see other examples of this trust in government as an honest judge in entries about food and drug safety and consumer product safety.)

The other thing worth noting is government’s steadfastness. A lot has changed in American politics since the mid-1970s, as Republican and Democratic administrations have come and gone, and Congress has changed hands numerous times. But the energy conservation programs have continued apace, and the savings they’ve created have accumulated year after year.

Government works best when it is all these things—promoter of positive externalities, reliable standard-setter, trusted truth-teller, steadfast agent of gradual change. And the results? More than 300 power plants that weren’t built, and an electricity curve that has been flattened. For these things, we can thank government.

More information:

https://www.energy.gov/eere/buildings/history-and-impacts

Give the credit to: federal government

Photo by KOMU News licensed under Creative Commons.

[…] again, we’ve seen how governments can produce great results, from lowering water consumption and flattening electricity demand, to reducing water and air pollution and revolutionizing agriculture by finding what works and […]